by Les Kendall

The Quarter-Guinea was only issued twice: once in 1718 by George I, and once in 1762 by George III. Both times it was a means to an end, and the end wasn’t exactly successful. This is the story of the Quarter Guinea, it’s problems and how Sir Isaac Newton moved from a bi-metallic standard towards the Gold standard to prevent a run on silver.

The Birth of the 1718 Quarter-Guinea

In 1717 we had a very famous name as Master of the Mint: Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727). Newton had worked at the Mint since 1696 as Warden, then as Master from 1699. His early tasks included eliminating counterfeiting and improving the quality of the coinage. But in 1717 he faced maybe a more serious problem.

The Value of Gold in Proportion to Silver

There was a lot of trade between Britain, Europe and the Eastern countries. In those days there were no sophisticated currency exchange rates or common currencies like the Euro; but all the traders understood the value of an ounce of gold or an ounce of silver. Thus, international trades were carried out using gold and silver coins.

This bimetallic standard had its risks. The main British gold coin was the guinea and at that time its value varied with the price of gold. Sir Isaac Newton, as Master of the Mint, wrote a report to the Lords Commissioners of His Majesty’s Treasury (you can download a PDF here).

The report highlighted how in Britain an ounce of gold could buy almost fifteen and a half ounces of silver but in East India you could buy an ounce of gold for twelve ounces of silver. So anyone who could afford it took silver to India to buy gold and then exchanged the gold for silver in Britain. Easy money, repeat as often as you can. Luckily there were only slow ships in those days.

Newton asked, and the King agreed, that the Guinea should be devalued. The reply on the 22 December 1717 was a Royal Proclamation (PDF here) “forbidding the exchange of gold guineas for more than 21 silver shillings“. Whether it was intended or not, Great Britain was moving toward the Gold Standard.

Shortage of Lower Denomination Coins

But the damage had already been done. Gold had flowed into the country but now silver supplies were desperately low. Silver shot up in price to the extent that the amount of silver in a silver coin was actually higher than the coin’s face value.

According to an inflation calculator, one pound (20 shillings) would be worth about £206 in today’s terms, so a Guinea was an lot of money and there was a requirement for smaller denominations.

As more profit could be made by melting the silver coins for their metal, lower denomination coins became scarce. There needed to be a replacement for the silver crown coin. Make it from copper and it would invite forgery; it had to be a precious metal.

Newton’s response was to make a gold equivalent to the silver crown (5 shillings): a gold Quarter-Guinea that would be worth and 5 shillings and 3 pence.

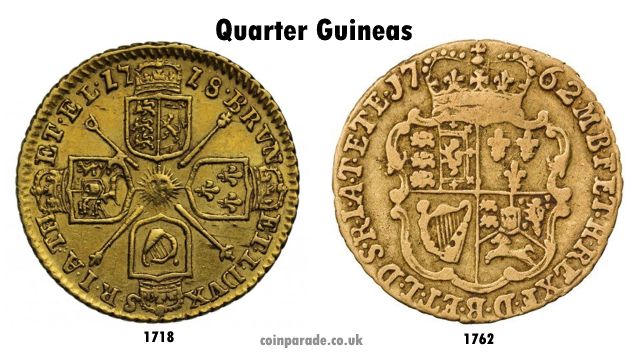

The new coin followed the same design and proportions of a full guinea. The Reverse shows crowned cruciform coats-of-arms with sceptres in the quarters and a Sun in the centre. A verbose Legend around with date at top. The Obverse shows the laurel head of King George I.

The problem was that to keep the proportions and get the correct weight of gold, the coin was just 16 mm in diameter and had a weight of just over 2.13 gram. Considering it was probably worth more than fifty pounds in today’s values it was a risky coin to have in your pocket and easily lost.

It was so unpopular that the Quarter Guinea wasn’t made again for 44 years.

The 1762 Quarter-Guinea

The 1762 version came about for a similar reason. Despite the fixed price of the Guinea, the silver prices were again rocketing. With silver being in such short supply it was again decided that the Quarter Guinea should be a gold coin.

History then repeated itself. To keep the proportions of the Guinea and Half-Guinea, the Quarter Guinea was therefore a small 22 carat gold coin with a diameter of 16 mm and a weight of 2.1 g.

Despite the small size, the coin itself packed as much detail as the Guinea coin itself, including the full legend text. The Obverse shows the portrait of George III by Richard Yeo (~1720–1779). The Reverse is a large and elaborate crowned shield. Some call this a “Four-fold arms design”.

The massive inscription is “M B F ET H REX F D B ET L D S R I A T ET E” (plus the date “1762”) meaning “King of Great Britain, France, and Ireland; Defender of the Faith, Duke of Brunswick and Lüneburg, Arch-Treasurer and Elector of the Holy Roman Empire”.

To compare, the Quarter-Guinea is a third lighter and 2 mm smaller than a modern 5 pence coin (which weighs only 3.25 gram). Imagine today having a £50 coin that small? You’d be terrified of losing it, and back in 1762 they were too. It, like its predecessor, was very unpopular.

The Quarter-Guinea was never made again.